In a recent post, I provided some tips for drafting Microbial Commercial Activity Notices (MCANs) to obtain approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the use of modified or synthetic microorganisms in chemical manufacturing. As summarized in that post and elsewhere in the blog, commercial use or importation into the U.S. of an “intergeneric” microorganism (i.e. one containing deliberate combinations of coding nucleic acids from different taxonomic genera) for certain industrial purpose would require submission and approval of an MCAN. Among the covered industrial purposes are manufacture of chemicals, fuels, enzymes or certain other specialty products, as well as environmental uses such as bioremediation or (in some cases) plant growth enhancement.

When properly written, most MCANs are approved routinely by EPA within the statutory 90 day review period. MCANs are strain-specific, usually covering only a single strain, although with prior EPA approval, an applicant can include up to 6 strains in a “Consolidated MCAN”. However, many of my clients or colleagues often ask the same question: whether improvements to a microbial strain that is the subject of an approved MCAN would require the submission of a new MCAN. It’s no surprise why this question almost always arises: even once a company has developed a microbial strain meeting its requirements for commercial use, the company will continue to conduct research on the process with the goal of developing improved strains that can produce the desired product more economically or impart the desired effect more efficiently. This type of R&D is often a continuous process that can lead to iterative changes to the original organism over a several year period, making this a question of potential ongoing concern to many companies.

Unfortunately, there is no single answer to this question since it depends on the extent and nature of the modifications made to the original approved strain. In fact, the determination can only be made by EPA, based on information the company provides. EPA has established a procedure under which companies can make such requests, based on the longstanding practice of “Bona Fide” inquiries under TSCA. The primary purpose of Bona Fide requests, as originally intended and used for many years in its oversight over chemical substances, is for companies to ask EPA whether a chemical substance which is not found on the public portions of the TSCA Inventory might be found on the confidential Inventory, so that premanufacture notification might not be needed for commercialization of the substance. When adopting the biotechnology regulations under TSCA, EPA established the procedures for Bona Fide requests for microorganisms, and in 40 CFR 725.15, the agency included the following statement regarding one scenario for such requests:

Persons intending to conduct activities involving microorganisms may inquire of EPA whether the microorganisms they intend to manufacture, import, or process are equivalent to specific microorganisms described on the Inventory.

Note that a microorganism goes onto the TSCA Inventory once an MCAN is approved and EPA is notified that commercialization of the microorganism has begun, so that an inquiry of whether the new microorganism is “equivalent to” a microorganism on the Inventory is the same as asking if the organism is equivalent to the microorganism described in a prior MCAN.

Section 725.15(b)(2) of the regulations specifies the information that should be included in a Bona Fide request for a microorganism, including for the purpose of clarifying the status of improvements to approved organisms, and in Attachment 2 to the 1997 Points to Consider document, EPA provided additional detail about how the Bona Fide requests should be made. The regulation identified the following items of information that should be included in a request.

(i) Taxonomic designations and supplemental information required by §725.12.

(ii) A signed statement certifying that the submitter intends to manufacture (including import) or process the microorganism for commercial purposes.

(iii) A description of research and development activities conducted with the microorganism to date, demonstration of the submitter’s ability to produce or obtain the microorganism from a foreign manufacturer, and the purpose for which the person will manufacture (including import) or process the microorganism.

(iv) An indication of whether a related microorganism was previously reviewed by EPA to the extent known by the submitter.

(v) A specific description of the major intended application or use of the microorganism.

This information can be submitted to EPA in a brief letter describing the new strain(s) and stating the basis for the company’s conclusion that the original MCAN could be judged to cover the new strain (the letter can be submitted confidentially via EPA’s CDX server). Item (iv) is the most relevant to the question at hand, and in such requests it would be desirable for a company to make its strongest arguments for the equivalence of the new strain to the original strain, and that the new modifications would not change the potential risks of the organism as EPA assessed in the original MCAN.

Although the actual determination of whether a new MCAN is needed for an improved strain must come through consultation with the EPA, it is possible to make some general statements about what types of modifications would or would not be judged to need a new MCAN, based on my general knowledge of EPA policy and my specific prior experience with Bona Fide requests. I have assisted clients with four prior Bona Fide requests, which had the following outcomes:

- A microorganism having the same intergeneric coding sequence and identical regulatory sequences, but differing from the MCAN organism solely in deletions and regulatory controls of endogenous genes, was judged to be covered by the prior MCAN.

- A microorganism modified solely by directed evolution of the approved MCAN organism (i.e. with no deliberately introduced changes to the original intergeneric sequences) was judged to be covered by the prior MCAN.

- A microorganism containing an additional copy of the same intergeneric gene contained in the MCAN organism, but differing in regulatory sequences and site of integration of this gene, was judged not to be covered by the prior MCAN. A new MCAN was needed for this microorganism.

- A microorganism engineered to express the same protein as in the approved MCAN, with the same regulatory sequences, but where the gene was modified to have a different coding sequence resulting in a protein having a different amino acid sequence than the protein encoded by the original MCAN strain, was judged not to be covered by the prior MCAN. A new MCAN was needed for the new microorganism.

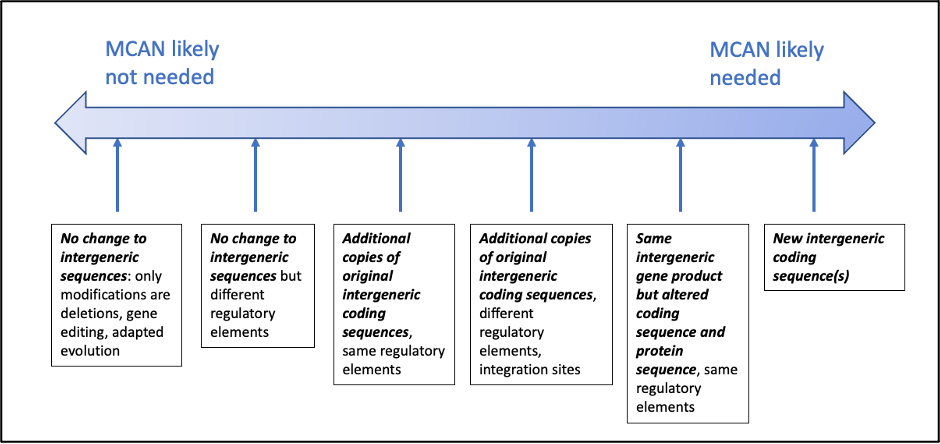

It is possible to view the likelihood of success to be a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum, changes to the original MCAN organism solely by gene editing, deletions, or directed evolution, without appreciably changing the make-up of the organism, its expressed gene product, or the intended use, would be the likeliest to be judged to be covered by the original MCAN so that a new MCAN would not be needed. At the other end, organisms containing entirely new intergeneric sequences, or deliberately-modified versions of the original intergeneric sequences, would be the least likely to be covered by the original MCAN, so that a new MCAN would likely be needed. Between these two extremes, other changes to the original MCAN organism would be more or less likely to be judged to be covered by the original MCAN. This spectrum can be shown as in the figure below, with the express caveat that this figure is for illustrative purposes only, and is based on our understanding of EPA policy, but should not be interpreted as binding legal advice.

Schematic figure showing the spectrum of changes to a microorganism covered by an approved MCAN that might be judged to either be covered by the approved MCAN or which might need a new MCAN. This figure does not purport to show or predict actual probabilities of either outcome, which can only be ascertained by consultation with the EPA on the specific circumstances of each case.

In my experience, preparing the needed information for such a Bona Fide request should not require too much preparation time inside the company, and EPA can usually respond within 2-3 weeks of the request, sometimes sooner. If EPA determines that the new strains are covered by the original MCAN, then your work is done, at least until further improvements are made to the strain. If EPA determines that a new MCAN is needed, the information included the Bona Fide letter can be used in the drafting of the new MCAN, so in either case the time spent preparing the Bona Fide request is not wasted time.

I would be happy to answer any questions you may have on how to prepare and submit an Bona Fide request, as well as to assist your company in the planning and preparation of any needed MCAN submissions.

D. Glass Associates, Inc. is a consulting company specializing in government and regulatory affairs support for renewable fuels and industrial biotechnology. David Glass, Ph.D. is a veteran of over thirty-five years in the biotechnology industry, with expertise in industrial biotechnology regulatory affairs, U.S. and international renewable fuels regulation, patents, technology licensing, and market and technology assessments. In addition to his work as a consultant assisting industrial biotechnology companies prepare for and comply with government regulations, he has served as Director of Regulatory Affairs for Joule Unlimited Technologies and Vice President of Government and Regulatory Affairs for BioTechnica International. Dr. Glass has extensive experience with the biotechnology regulations of the U.S. EPA and other agencies, and has coordinated or assisted in the preparation and submission of 18 successful Microbial Commercial Activity Notices and several other biotechnology submissions in the U.S. and other countries. Dr. Glass holds a B.S. in Biological Sciences from Cornell University and a Ph.D. in Biochemical Sciences from Princeton University.